Americans marvel at the commitment and courage of our nation’s healthcare providers as they struggle under enormous pressures to care for the sick and dying during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to the doctors, nurses and paramedics who were already actively working to care for COVID-19 victims, thousands more have come out of retirement to provide assistance to those on the front lines, choosing to put themselves directly in harm’s way to help.

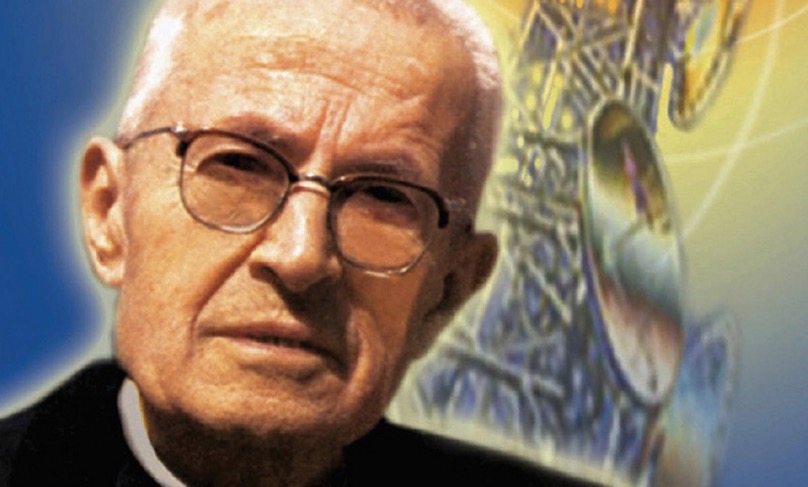

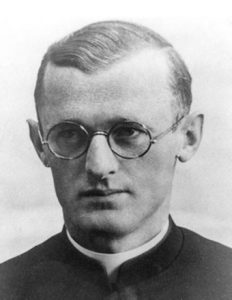

While volunteers in times of medical emergency do not have an obvious patron saint, they might very well find one in Blessed Engelmar Unzeitig, known as the “Angel of Dachau.”

Born in what is now the Czech Republic in 1911, Hubert Unzeitig joined the Marianhill Missionaries at age 18. After completing his studies in theology and philosophy, he was ordained in 1939 and given the religious name Engelmar. A month later, World War II began.

Although he desperately wanted to serve as a missionary among the poor, he was assigned as a parish priest first in Austria, then in the Bohemian Forest region of Germany. It was there Father Engelmar encountered the Hitler Youth, who eventually reported him to the Nazi regime for his homilies, in which he defended the Jewish people and criticized their increasingly dehumanizing treatment. Father Englemar was arrested by the Gestapo on April 21, 1941 and sent to the concentration camp at Dachau. He was 30 years old.

Dachau was a unique place among the Third Reich’s concentration camp scheme. Established in 1933, it initially was used exclusively for enemies of the state. Beginning in 1940, Nazi leadership chose Dachau as a designated site for the consolidation of religious ministers and began a transfer of those being held from other camps to Dachau. In total, 2,720 men were incarcerated, 95% of them Catholic priests (the vast majority of them from Poland). The remaining men were Jehovah’s Witnesses and Lutheran or Evangelical Protestant pastors (most of these from Germany). Father Engelmar arrived in Dachau on June 3, 1941, was assigned inmate number 26147, placed in Barracks #26, and given a badge to wear on his camp uniform. Distinct from the yellow star denoting Jews or the black triangle designated for Gypsies and prostitutes, Father Engelmar was given a red triangle, the symbol reserved for “rescuers of Jews,” political prisoners and Catholic priests.

From the moment of his arrival at Dachau, Father Engelmar entrusted himself to God’s will and to His Divine Providence. In August 1941, he was permitted to write a letter to his sister, Regina, and assured her, “God directs everything with wonderful wisdom. Only we don’t always know immediately what everything is good for.”

Father Engelmar’s confidence in God’s care for him and his desire to help others manifested itself almost immediately; he began to learn the Russian language, so he could minister and care for Eastern European inmates, he often gave up his own food rations for those who were hungrier than he.

The treatment priests received in Dachau ranged from tolerable to torturous, depending on the day and the commandant’s mood. One historical account of the priests’ barracks notes:

“Priests at Dachau were not marked for death by being shot or gassed as a group, but over two thousand of them died there from disease, starvation, and general brutality. One year, the Nazis ‘celebrate'” Good Friday by torturing 60 priests. They tied the priests’ hands behind their backs, put chains around their wrists, and hoisted them up by the chains. The weight of the priests’ bodies twisted and pulled their joints apart. Several of the priests died, and many others were left permanently disabled.”

In late December 1944, Dachau experienced an outbreak of typhoid fever. Those who contracted typhus were isolated into separate barracks and left to die alone. Father Engelmar (faithful to the motto of the Marianhill Missionaries, “If no one else will go: I will go!”) offered to enter the typhoid barracks, along with 19 other priests from the clergy barracks. No medicines and no protection from the typhoid infection were offered to them, yet they tended to the sick and dying with tenderness, bathing, comforting and anointing them. Although he knew this mission would likely be his last, Father Englemar nevertheless maintained his faith and confidence in a good God. In January 1945, he again wrote to his sister, “We must never forget, you see, that everything which God sends or permits is meant to contribute to our good.”

Of the 20 priests who volunteered for the typhoid barracks, 18 died. Father Engelmar was among them, passing away on March 2, 1945. He was 34 years old. Six weeks later, American forces liberated Dachau.

Years later a miraculous cure from cancer, credited to Father Englemar’s intercession, was investigated in the Diocese of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. It involved a man who had been among the American troops that liberated Dachau.

Pope Benedict XVI declared Father Englemar venerable in 2009 and Pope Francis designated him a martyr, killed “in hatred of the faith.” Beatified in 2016, Blessed Englemar’s feast day is March 2.

Mary Hallan FioRito is the Cardinal Francis George Fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and the de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture at the University of Notre Dame.