One of the more contemporary fields of theological study in the last century has been the discipline of ecclesiology, which studies the Church. This is a vital area of study because if Jesus intended to found a Church, then we must look to revelation to understand what this Church looks like and what Christ intended.

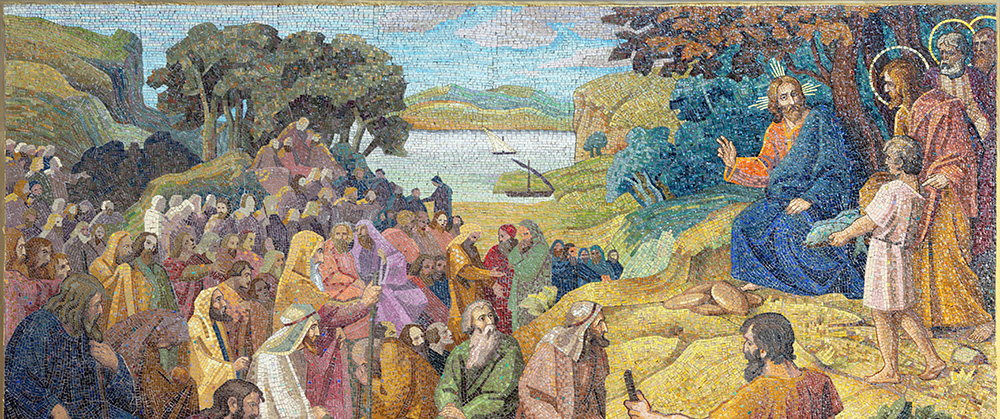

Ecclesiology, therefore, begins with the basic question: Did Jesus intend to found a Church? The New Testament, as well as early Church history, makes this abundantly clear, and it is relatively well-accepted among both Protestants, Catholics (and other Christians, like the Orthodox, for that matter) that Jesus did, in fact, establish a Church as a body of believers called to gather around his teachings and live them out as a manifestation of the Kingdom of God.

That is where Protestants and Catholics agree. But what the Church looks like — i.e. her external features — is where major disagreement begins. For Catholics, there are essentially two aspects that are necessary for a Church to be a Church. First, it must have a hierarchical structure, centered upon the bishops and pope; second, it must have the sacraments. These are the two essential features for an ecclesial structure to be called a Church.

The hierarchical structure is vital to the Church because without the bishops, there is no Church. The bishop of each diocese is the symbol of unity in his local diocese. Communion among the bishops comes from unity with the pope, as the one who holds the Church’s unity together in communion. The pope is the guarantee that we are all part of the same Church that Christ instituted. The bishops, then, exist as ministers of the Church’s unity. Through them we have apostolic succession, which means that their office is traced back all the way back to Jesus’ apostles. As presiders over the Church’s unity, the bishops oversee things such as the sacraments, which are at the core of the Church’s life. Without the bishops, there are no sacraments, and without both, there is no Church.

The Church’s hierarchy exists to facilitate the unity of the Church, which exists as a communion.This is to say that each member exists and lives for all the other members of the Church. Each of us has a mission in the life of the Church, called to be in service to one another. Episcopal leadership being solely defined by power has no place, since the power attached to the bishop’s office is only given to achieve and guarantee the Church’s unity.

There are other aspects of ecclesiology equally vital: What does it mean to say the Church is “one, holy, catholic,” too? How do we understand, for example, that the Church is holy when sinful at the same time? The Church’s holiness is possible only because her head, Jesus Christ, our Lord, is holy, and we are the members of his body. As sinners, clergy and laity can become holy through Christ alone.

The Church is first and foremost a sacrament — that is, a visible sign that makes effective and visible the invisible reality she signifies. The mission of the whole Church is a mission for the life of the whole world. All those who are baptized into Christ are to make Christ’s salvation not only visible but effective to all the world. This is because the Church is inherently missionary by nature, an idea reiterated time and again by Pope St. Paul VI. It is the task of every single Catholic, then, to be cooperators with Christ’s saving mission, through word and deed. The whole of our lives are to be defined by Christ. That means Christianity cannot be simply a hobby — an addition to one’s life — but a whole way of being. Because the Church is a sacrament, her members – always and everywhere — have the opportunity to be a sign by which the saving actions of Jesus are made effective in the lives of others.

Father Harrison Ayre is a priest of the Diocese of Victoria, British Columbia. Follow him on Twitter at @FrHarrison. Read more in the “Introduction to Theology” series here.