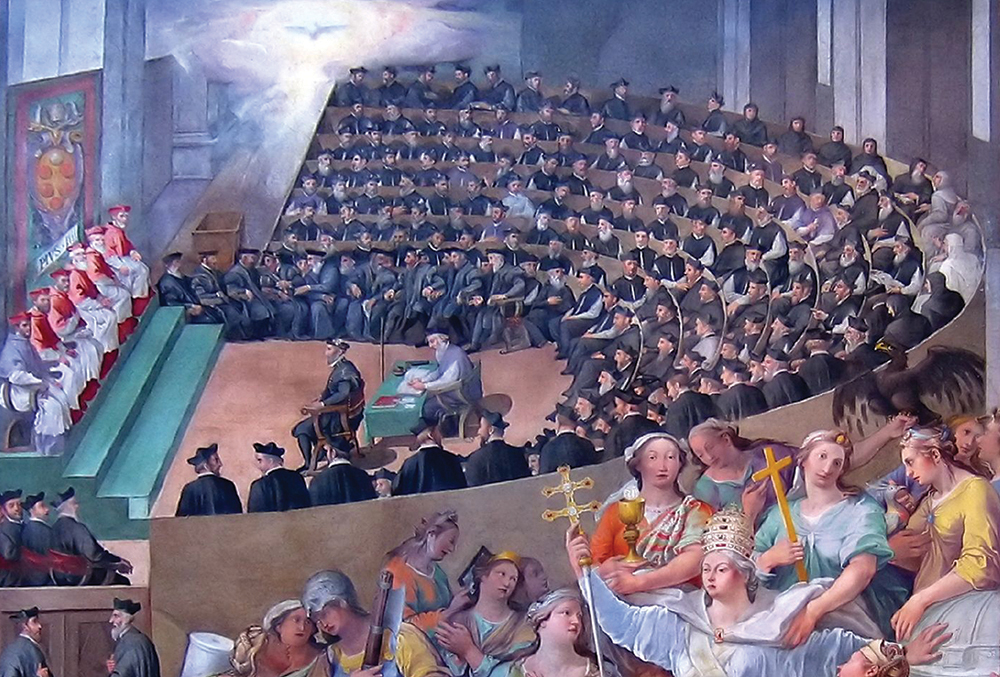

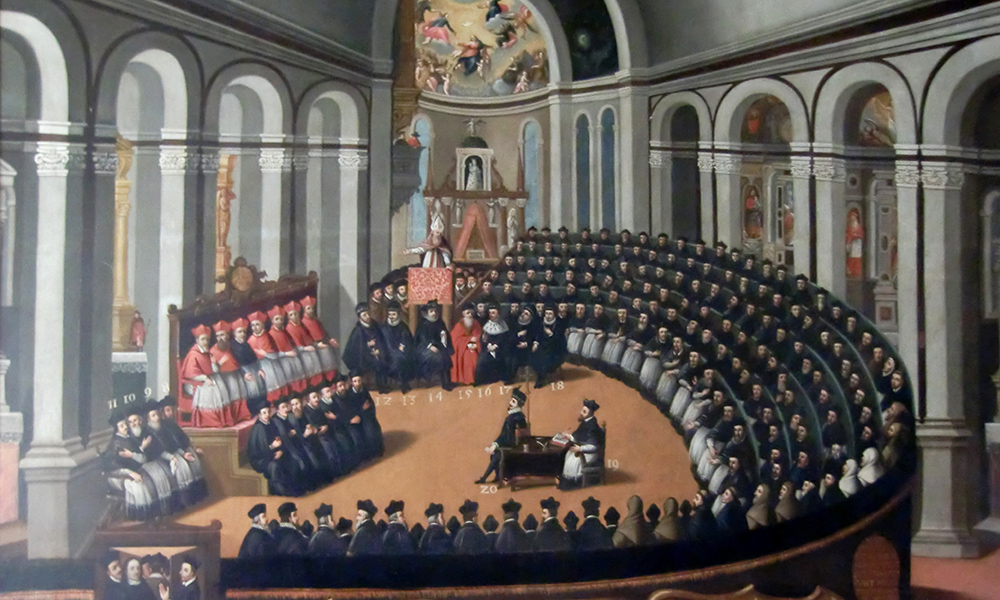

“The latest ecumenical councils — Trent, Vatican I, Vatican II — applied themselves to clarifying the mystery of the faith and undertook the necessary reforms for the good of the Church, solicitous for the continuity with the apostolic tradition.” — Pope Blessed John Paul II, Discourse, Oct. 22, 1998

In the middle of the 16th century, the Catholic Church was in need of reform and renewal, and while the Church acknowledged these problems and had begun reforms, the corrective actions were not quick enough or deemed serious enough to stem large numbers of Catholics from leaving the Church. Martin Luther’s revolt and the subsequent Protestant revolution in the mid-1500s accelerated the reforms that were eventually realized through the Council of Trent. This council, the 19th ecumenical council in Church history, not only dealt with corruption but, more importantly, effectively refuted the heretical teachings and anti-Catholic attacks launched by Protestants.

Few ecumenical councils have left more of a long-term impact on defining and reforming the Catholic Church than did the council held in several different sessions at Trent, Italy, between 1545 and 1563. From the opening to closing ceremonies, the Council of Trent lasted 18 years, but the bishops were in session for just a little more than three years. Of course, the council was not intended to be spread over 18 years, but the work of the bishops was interrupted by plague, wars, the deaths of four popes and a lack of interest from Pope Paul IV (1555-1559), who thought he could achieve reforms without the council.

The results of that historic gathering are still debated by Catholics and non-Catholics alike, but the debates are matched by a host of myths as to what the council fathers at Trent did or did not do.

One long-running myth claims that the popes of the 16th century, fearing a loss of prestige and power, resisted calling a general council to deal with Church abuses and corruption. While 15th- and 16th-century popes were indeed cautious, Pope Paul III (1534-1549) tried three times to convoke a Churchwide council. His efforts were repeatedly stymied by political squabbles and unenthusiastic support from European monarchs and princes.

Pope Paul III first summoned a council in 1537 to be held at Mantua, Italy. Emperor Charles V, ruler of the Holy Roman Empire, allegedly did not like the location. In the end, the city of Trent was chosen, and the council finally opened in December 1545. In sum, there long had been discourse about the need for a Church council, but it was the monarchs, not the popes, who delayed the event. This, of course, is just one of the myths associated with the Council of Trent

Myth: Trent ended the practice of indulgences.

Fact: The practice of indulgences was not ended, continues today and is defined in the current Catechism of the Catholic Church (see Nos. 1471-1484). The XXV session of Trent affirmed Church authority to issue indulgences and condemned “those who assert that they [indulgences] are useless or who deny that the Church has the power to grant them.” The council did eliminate the misuse and the so-called selling of indulgences which Martin Luther (and others) found repugnant.

Myth: Trent added seven books to the Old Testament.

Fact: Beginning in the fourth century there was Churchwide consensus that the Old Testament contained 46 books. That number of books is identified in the ancient Alexandrian (Christian) list of Scriptures as opposed to the Palestinian (Jewish) list that has fewer books. The decision to favor the Alexandrian list was subscribed to at the Council of Hippo in 393 and reaffirmed at the Council of Carthage in 397 (these two councils were smaller in nature and are not listed among the Church’s 21 ecumenical councils). When Luther’s followers translated the Bible into German, they left out the books of Tobit, Judith, First and Second Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach and Baruch, as well as parts of Daniel and Esther. Protestants also made changes to the New Testament text which, like the Old Testament omissions, conflicted with their beliefs.

Myth: The Council of Trent directed Catholics not to read the Bible.

Fact: This is not true. The bishops confirmed that the Latin Vulgate Bible, in use by Christians for over a thousand years, was the correct version for Catholics to use. It is true that the Church fathers at Trent were concerned about the numerous new translations of Scripture that were filled with error and misinformation and lacked proper and authentic notes. Consequently, they did mandate that only with permission of the pope could versions other than the Vulgate be read.

Myth: Trent resulted in sweeping changes to Catholic teaching.

Fact: There were no changes made to Catholic teaching at the Council of Trent. The No. 1 priority was to defend clearly Catholic beliefs under attack by Protestants, which included: the belief that Christ instituted seven sacraments, not two as asserted by Luther; that justification was achieved by faith and good works, not by faith alone; that the deposit of faith included both the sacred Scriptures and sacred Tradition, not the Scriptures alone; that Communion of one kind for laypeople is sufficient to receive the Real Presence; that the traditional teachings on transubstantiation and original sin are correct; that purgatory does exist; that Masses for the dead are appropriate. These were affirmations, not changes, to Catholic beliefs. In a like manner, the conciliar decrees that defended the Mass were based on unchanging truths and revelation, not on innovation.

Myth: Trent “damned to hell” those who do not agree with the decrees they issued.

Fact: The canons, or decrees, issued by Trent all include the term “anathema.” For example, the Council of Trent, session XXII, canon V, reads: “If anyone saith, that it is an imposture to celebrate Masses in honor of the saints and for obtaining their intercession with God, as the Church intends, let him be anathema.” The word anathema is a Greek word meaning to separate, suspend or set aside, not “damn to hell.” The Church does cut off or excommunicate Catholics who consciously and publicly deny the canons of Trent because the canons affirm the teachings of Christ. These Catholics are welcomed back when willing to be reconciled with the Church’s teachings.

Myth: The Council of Trent acknowledged that women have souls.

Fact: This was and is the most far-fetched of any myth associated with the council. That women have souls was never questioned by the Church, nor was it addressed by the bishops at Trent. This wild accusation seems to have its roots in St. Gregory of Tours’ “History of the Franks” (Book VIII, Ch. 20). This history records that at the Synod of Mâcon in 528 one of the bishops questioned whether the Latin word homo, or man, as used in the Old Testament, includes both male and female. The issue was clarified that indeed women are included in the term. There was never an official canon or decree released, and whatever was discussed had nothing to do with whether or not women have a soul. In the 17th century, anti-Catholics attempted to distort the discussion at Mâcon and publicly claimed that the Mâcon bishops had formally addressed — even voted — as to whether or not women have a soul. Through the years this myth has been exacerbated and skewed so as to connect it with the council at Trent. Even today some Internet sites claim that the Church once debated whether or not women have souls.

Myth: Trent resulted in a rigid Church, one that lacks both diversity and stymies fresh ideas.Fact: The bishops at Trent, like all Catholic bishops, saw themselves as guardians of the deposit of faith, the faith of Jesus Christ. What was true when Jesus walked the earth was true in the 16th century and is true today, and the Church makes no apologies for that position. Since the opening session of Trent there have been 44 popes, each with his own perspective, each with his own administration, each with his own ideas — but none have broken with the teachings of Jesus.

The Council of Trent and the Reform of the Church

While Church fathers at Trent clarified but did not change Catholic teachings, they did make many lasting reforms in the organization and administration of the Church. These reforms included:

– Ending the practices of simony, nepotism and pluralism.

– Limiting bishops to control of only one diocese or holding more than one ecclesiastical office at a time, which had not previously been the case. Bishops were expected to reside and govern their diocese and regularly visit each parish; lengthy absences required the pope’s approval. Every bishop was obligated to maintain high moral standards, live frugally and avoid excess.

– Requiring strict discipline within religious orders and placing monasteries under the jurisdiction of the bishop, rather than the pope.

– Giving special attention to the education of the clergy, including the goal of establishing a seminary in every diocese. Celibacy was upheld, bishops were responsible to select and mentor men for the priesthood, and those men could not be ordained before age 25.

– Promoting the development of the Roman Missal to standardize the Mass and a catechism containing a concise summary of Catholic beliefs.