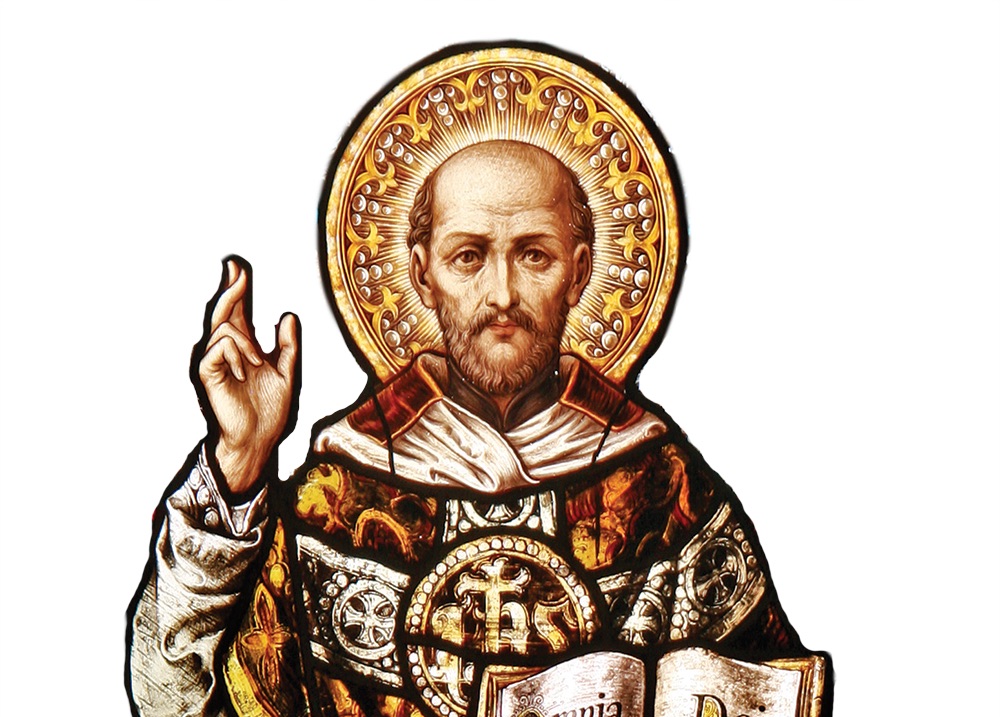

Ignatius of Loyola was born into a family of Basque nobility in the family castle of Azpeitia. He was the youngest of the 13 children of Beltran de Loyola and Marina Saenz de Licona. From his earliest years, Ignatius was enchanted by dreams of chivalry and adventure. His own father had performed deeds of valor in the final years of the Reconquista, the Christian reconquest of Spain from the Moors. His oldest brother, Juan, had sailed with Columbus on the discoverer’s second expedition to the New World. With these models before him, it is no wonder that Ignatius longed to sacrifice himself for a great king, to serve faithfully a beautiful lady and to win immortal fame in the eyes of the world.

As a young man he tried to live out his notion of the gallant cavalier: He was ambitious, vain, prickly about his honor, a gambler, a fighter and a sexual adventurer. At age 26, he fought against a French army in his first — and last — battle. A cannonball struck Ignatius’ legs, shattering the one and wounding the other. Ignatius and his comrades surrendered to the French commander, who spared their lives, sent his own doctors to treat Ignatius, then provided an escort to carry him home to Azpeitia.

To help him pass the time during the long weeks of convalescence Ignatius read the only two books in the house — a life of Christ written by Ludolph the Carthusian and “The Golden Legend,” Jacobus de Voragine’s collection of saints’ lives. As he read these books, Ignatius’ heart was touched by grace: He became ashamed of the vanity, pride and lust that had ruled his life thus far. Ignatius had undergone a conversion, but he had not abandoned his chivalric ideals of suffering and self-sacrifice — instead, he had shifted his focus from winning honor in this world to winning souls for God.

Ignatius’ conversion came during one of the greatest crises the Catholic Church has ever faced: the Reformation. The Protestant revolt had split Europe into two religious camps, shattered the unity of western Christendom and cost the Church hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of souls.

To restore and revitalize the Church, Ignatius envisioned a new community of priests and lay brothers who would be deeply educated in the Catholic faith, in theology and in sacred Scripture. They would be skillful teachers, wise spiritual directors and gifted preachers. He would send out these men across Europe to reclaim Christians who had left the Catholic Church and to bolster the faith of Catholics who were perhaps uncertain about or poorly educated in the essentials of their faith.

Ignatius’ method worked. Jesuits schools and colleges became the pride of the Catholic world — it was not unusual for Protestant families to enroll their sons in them. Jesuit preachers attracted large crowds and brought countless souls back to the Church. And Jesuit missionaries were fearless, traveling into Protestant lands where some, such as St. Edmund Campion, met a martyr’s death, or much farther afield, to the New World or to Asia.

Today, much of the Western world is once again in a spiritual crisis. Religious practice is shrinking in Western Europe, Canada, the United States, even in Latin America. To reverse the trend, Blessed John Paul II called for a New Evangelization, a new missionary spirit to reclaim souls for God. Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI tried to advance John Paul’s vision, and Pope Francis is doing the same. A model for the New Evangelization is St. Ignatius of Loyola, whose Jesuits did so much to revitalize the Church and save souls.

St. Ignatius of Loyola is the patron saint of retreats, soldiers, the Society of Jesus and of the Basque country. His feast day is July 31.

Craughwell is the author of more than 30 books, including “Saints Behaving Badly” and “This Saint Will Change Your Life.”