Christian sacraments and sacramentals, filled with symbolism, are steeped in historical and scriptural richness. In their celebration, a host of everyday substances are used, serving as signs and symbols of…

Christian sacraments and sacramentals, filled with symbolism, are steeped in historical and scriptural richness. In their celebration, a host of everyday substances are used, serving as signs and symbols of the much deeper realities they represent.

Oil is one of the array of rich symbols we have in our Christian tradition. Today, the Church uses three types of holy oils for a host of purposes. The multifaceted use of oil among ancient peoples is referenced in a variety of scriptural passages. These include use in preparing food for nourishment (see Nm 11:7-9) or as lamp fuel (see Mt 25:1-9). A medicinal use for oil is found in both Old and New Testaments (see Is 1:6; Lk 10:34), or for physical embellishment (see Ru 3:3). Oil is also useful in preparation of bodies for burial (see Mk 16:1) and as a ritual anointing for welcoming guests (see Lk 7:46).

The Church’s rites prescribe that the oils are normatively blessed (or consecrated, in the case of chrism) at the Chrism Mass each year. All priests may bless the oil of catechumens and oil of the sick “in case of true necessity.”

As evidence of their fruitfulness and importance in our sacramental life, oils take center stage when they are blessed and consecrated just before Easter, at what is called the Chrism Mass. This provides for the new oils to be used at the sacraments of initiation at the Easter Vigil.

The Chrism Mass

Rubrics for the Chrism Mass in the Roman Missal include the time when the Mass is to be celebrated — namely, on Holy Thursday morning. The Chrism Mass is a concelebrated Mass with diocesan presbyterate who are the bishop’s “witnesses and the co-workers in the ministry of holy chrism.” It is also at this liturgy that the priests renew their priestly promises in their bishop’s presence. To achieve this, then, the missal concedes that if Holy Thursday morning is difficult, then “the Chrism Mass may be anticipated on another day, but near to Easter.”

The three oils are presented to the bishop with the bread, wine and water at the preparation of the gifts. The entire rite of blessing and consecration may be celebrated at this time, “for pastoral reasons.” However, the Introduction of the Rite of the Blessing of Oils and Rite of Consecrating the Chrism states that it is the Latin rite’s ancient tradition to bless the oil of the sick at the end of the Eucharistic prayer, when, in early Christianity, fruits of the earth and the produce they yielded were blessed. In that case, then, the blessing of the oil of catechumens and the consecration of the Chrism takes place after Communion.

The instructions and prayers of the Chrism Mass help us gain a clearer knowledge and appreciation of the oils and what they signify. The collect of the Chrism Mass recalls that Christ was anointed with the Holy Spirit, and that we, who are “sharers in his consecration,” are to bear witness to him in the world.

Oil of Catechumens

The Introduction for the Rite of Blessing of Oils says the oil of catechumens extends the effect of the baptismal exorcisms: “Before they go to the font of life to be reborn, the candidates for baptism are strengthened to renounce sin and the devil.”

The notion of being strengthened by oil is scriptural. God’s anointing has fortified us in the battle of good versus evil (see Ps 45:8 and Heb 1:9) and enlightens our intellect from falsehood (see 1 Jn 2:27). The prayer of blessing for the oil of catechumens indicates these fruits when it asks God to “give wisdom and strength to all anointed with it,” going on to ask God to bring those anointed by this oil “to a deeper understanding of the Gospel” and gain God’s help in accepting “the challenge of Christian living.”

This oil can be traced back to the early Christian instruction the Apostolic Tradition, written in the early third century, which refers to it as the “oil of exorcism.” In the Rite of Baptism today, a prayer of exorcism is proclaimed over the candidate and is followed by the anointing with the oil of catechumens. The anointing with this oil, alongside a prayer of exorcism, may be administered during the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults (RCIA) to adults admitted to the catechumenate.

By the anointing with the oil of catechumens then, it can be said that the recipient gains God’s grace and help to overcome the power Satan and sin have over us and profess the Christian faith with boldness, all of which aims toward the newness of life received in baptism.

Oil of the Sick

The passage most often cited as a scriptural witness for sacramental anointing of the infirm is in the Letter of James (5:14). In Mark 6, Jesus gave the Twelve “authority over unclean spirits” (v. 7), and “they went off and preached repentance” (v. 12). The very next verse, however, indicates the use of oil in healing the sick in Christ’s name from even this apostolic age: “They drove out many demons, and they anointed with oil many who were sick and cured them” (v. 13).

The oil used most often by priests, its prayer of blessing reminds believers that healing of the sick comes about through Jesus Christ. Oil’s multifaceted purpose, mentioned earlier, is indicated when the prayer refers to oil as that “which nature has provided to serve the needs of men.”

As the Instruction of the Rite of Blessing of Oils says, in the anointing, “the sick receive a remedy for the illness of mind and body, so that they may have strength to bear suffering and resist evil and obtain the forgiveness of sins.” All who receive anointing with this oil receive God’s blessing, as the prayer of blessing says, so “that they may be freed from pain and illness and made well again in body, mind and soul.”

Sacred Chrism

Before consecrating the chrism, the bishop mixes the oil with balsam — a sweet, aromatic perfume used since ancient times, no doubt in connection to 2 Corinthians 2:15-16, where St. Paul refers to the fragrance of Christ that Christians must disperse everywhere they go. Then, before the prayer of consecration, the bishop breathes over the oil — indicative of the Holy Spirit’s descent through invocation.

The verb “consecrate” is applied to the action of making holy the chrism and indicates its use to spiritually separate, sanctify and purify its recipients. While the oil of the sick and the oil of catechumens may, in emergency, be blessed by any priest, this is not the case with chrism. “Consecrate” indicates, then, that only a bishop may bless it.

Christ’s holy name means “the anointed of the Lord.” The consecratory anointings in the Old Testament are for priests, prophets and kings — all of which point toward and prefigure Jesus Christ. He takes on this identity at the beginning of his public ministry, when in his hometown synagogue he read from Isaiah 61:1: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me” (Lk 4:18). And so the oil of chrism takes its very name from him and is the means by which Christians become sharers in his royal and prophetic priesthood. “We are called Christians because we anointed with the oil of God,” wrote St. Theophilus of Antioch in the second century.

There are two consecratory prayers optioned in the ritual, the first of which draws significant parallels between Christian use of this oil and similar biblical use of oil. The first prayer is one of thanksgiving for God’s gifts given in the past, foreshadowing those given through anointing with this oil. In fact in the third-century Apostolic Tradition, it is referred to as the “oil of thanksgiving.”

The strength Israel’s kings needed in governing earthly affairs with divine guidance was symbolized in their Old Testament anointing (see 1 Sm 10, Samuel’s anointing of Saul). The first of the consecratory prayers references King David twice — as he “sang of the life and joy that the oil would bring us in the sacraments,” and it was through him that God prophesied that “Christ would be anointed with the oil of gladness beyond his fellow men.” In history, a variety of Christian kings and emperors were anointed with sacred chrism by popes and bishops at their coronations.

In the case of Elisha, we learn of the biblical anointing of a prophet (see 1 Kgs 19:16). Recipients of sacred chrism will prophetically be “radiant with the goodness of life that has its source in (God).”

Priests and bishops today are anointed with sacred chrism at their ordinations. An Old Testament source for this practice is found with Aaron, Moses’ brother, whom he anointed a priest (see Ex 29:7 and Lv 8:12).

“Let the splendor of holiness shine on the world from every place and thing signed with this oil,” says the second of the consecratory prayers for chrism. Formerly, church bells were anointed on the inside with chrism and the oil of the sick on the outside. The ancient practice of using chrism to consecrate altars and churches remains in practice today.

Using oil to dedicate things to God has Old Testament roots (for examples, see Gn 28:18 or Ex 30:25-29). Altars are set aside for sacrifice and early in Christianity the altar became representative of Christ himself, the perfect sacrifice. And so, since Christ’s name means anointed one, it’s most fitting that the altar — which is a symbol of the Anointed One par excellence — itself is anointed. In dedicating a church building, a church’s walls are signed with chrism — since the building represents the anointed members of his Body, and, like us are called to be “holy, visible signs of the mystery of Christ and his Church.” More on this is found in the Rite of Dedication of an Altar.

Reception of Oils in Parishes

After their blessing or consecration, the holy oils are distributed to the parishes and institutions of the diocese, usually available immediately after the Mass for priests or parish representatives to retrieve. There is an optional rite for the reception of the holy oils in parishes, approved by the Holy See in 1989 for use in the United States. The rubrics were amended with the 2011 implementation of the third edition of the Roman Missal, although the text for the rite remains the same.

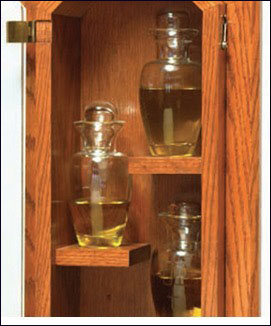

In parishes, oils are generally kept in a repository called an ambry. EyePix

In conjunction with the Evening Mass of the Lord’s Supper on Holy Thursday, the rite’s introduction from the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops discusses a fitting time for the oils to be received: “The first option for the reception of the holy oils is before the Mass begins, but according to pastoral necessity and any guidelines of the diocesan Bishop, ‘another time that seems more appropriate’ could also include the offertory procession (as in the original ritual) or perhaps before the Penitential Act.” This optional rite is simple and straightforward, recommended and appropriate. It includes the presentation of each oil by name and a brief invocation wherein each oil’s purpose is announced by the celebrant.

The holy oils are to be kept in a suitable place, a repository called an ambry that typically is near the baptismal font. Old oils are to be disposed of in a respectful and dignified manner — the most typical way is to burn them. One way to do this is to burn them in the fire prepared at the Easter Vigil. In some cases, they are returned for proper disposal by diocesan officials.

MICHAEL R. HEINLEIN is editor of Simply Catholic. Email him at mheinlein@osv.com. Follow him on Twitter @HeinleinMichael. This article originally appeared in The Priest magazine.