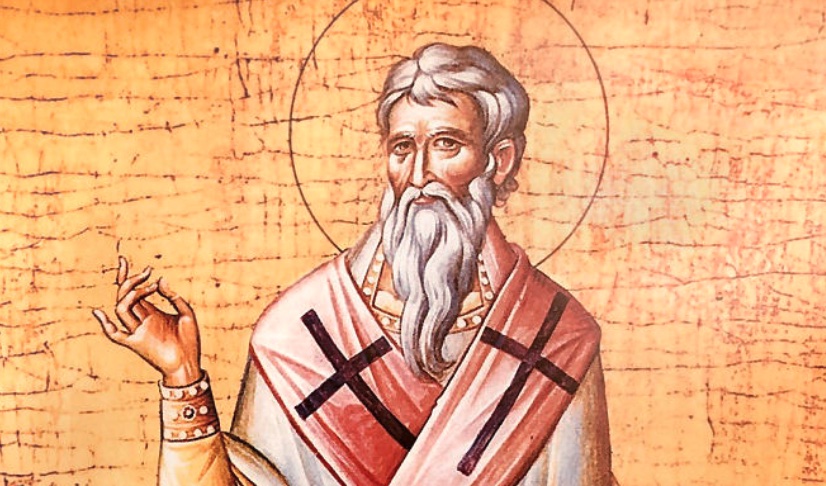

How do Scripture and Tradition work in the Church? What does their relationship look like? To answer this, it’s perhaps best to begin with one of the great heroes of the Faith, St. Irenaeus of Lyons, who was a bishop in France at the turn of the third century.

Irenaeus was writing when — if you were to consider the vast religious landscape of his tumultuous time — it would have been difficult, if not impossible, to discern one single form or expression of the Christian faith. Rather, it was a time (not unlike our own) when there were several competing versions of Christianity vying for believers’ allegiance. These different “schools,” as St. Irenaeus derisively called them, each had different attitudes toward the Gospel, different ideas about Jesus and different approaches to the Scripture. Some “schools” thought Jesus was a shapeshifter, for instance; some thought he wasn’t fully human; others thought he wasn’t fully God. Some believed all knowledge of God came entirely from personal inspiration while others had different theories of spiritual enlightenment. All sorts of slight nuances distinguished these very similar but still quite different versions of Christianity. It really was a free market of Christianities, so to speak, in these early centuries. And, it was in this environment that Irenaeus asked a very simple question: How does one tell the authentic Christian faith from the inauthentic, the true faith from the false?

His answer was simple: because the apostles said so. As St. Irenaeus put it: “We have learned from no others the plan of our salvation than from those through whom the Gospel has come down to us, which they did at one time proclaim in public, and at a later period, by the will of God, handed down to us in the Scriptures, to be the ground and pillar of our faith.” In pointing to what we today recognize as Scripture, Irenaeus wasn’t just holding up the texts, but those who wrote them. Matthew wrote his Gospel; Peter and Paul preached in Rome; Mark, Irenaeus said, wrote down what Peter preached; Luke was influenced by Paul’s preaching; after that, John wrote his Gospel at Ephesus. “These have declared to us that there is one God,” he wrote (Against Heresies, No. 3.1.1-2). Irenaeus’ simple argument was that in a competitive religious atmosphere — this free market of Christianities — authentic belief, right belief (“orthodoxy”) takes its stand on these Gospels and these particular texts written by these particular people whose lineage we can trace, whom we know. That is, to guarantee correct belief, the Scripture had to be with and within the Church. It had to be accepted as apostolic Scripture.

Taking this stand is important, Irenaeus argued, because otherwise, one risks following whims and myths and personal and collective distortions. Or, one risks pridefully listening to oneself other than the truth. Those who go it alone, apart from the Church, Irenaeus said, teach what “neither the prophets preached, nor the Lord taught, nor the apostles handed down.” Instead, “they boast rather loudly of knowing more” about the Faith than others, referring to “unwritten works; and as people would say, they attempt to braid ropes of sand. They try to adapt to their own sayings in a manner worthy of credence, either the Lord’s parables or the prophets’ sayings, or the apostles’ words, so that their fabrication might not appear to be without witness.” They twist the Scripture, Irenaeus said, disregarding “the order and the connection of the Scriptures.” They “disjoint the members of the truth;” they “transfer passages and rearrange them; and, making one thing out of another, they deceive many by the badly composed fantasy of the Lord’s words that they adapt” (Against Heresies, No. 1.8.1). Distorting Scripture, taking stuff out of context, bending words: that’s the problem, Irenaeus said, that follows from abandoning apostolic tradition. That’s what comes from reading the Scripture without tradition outside the Church. It may look a lot like the true faith, but it’s subtly ruined. St. Clement of Alexandria described it once, this subtlety of subversion, saying how some people can “twist the Scriptures by their tone of voice to serve their own pleasures” (Stromateis, No. 3.39.2). That’s the sort of danger one falls victim to, Irenaeus says — cutting and pasting, twisting fragments of true faith into false faith.

But that’s not how a person engages the Scripture if they’re seeking the genuine Christian faith. Rather, one seeks the single voice of the Church, the one faith “though disseminated throughout the world.” The Church, Irenaeus said, “carefully guards this preaching and this faith, which she has received, as if she dwelt in one house. She likewise believes these things as if she had but one soul and one and the same heart; she preaches, teaches and hands them down harmoniously, as if she possessed one mouth.” Preachers of the true faith will not make things up and will not be innovative, Irenaeus says. Orthodox preachers will not claim new personally discovered insights. “Neither will any of those who preside in the churches, though exceedingly eloquent, say anything else (for no one is above the Master); nor will a poor speaker subtract from the tradition. For, since the faith is one and the same, neither he who can discourse at length about it adds to it, nor he who can say only a little subtracts from it” (Against Heresies, No. 1.10.2).

That’s the mark of the true faith: that it’s connected to the Church and that it’s traditional, not esoteric or charismatically progressive. In the whirl of competing Christianities, Irenaeus hunkers down within apostolic tradition and upon this apostolic Scripture found only in the Church. For Irenaeus, there is a stark difference between an orthodox approach to the Christian faith and those not orthodox. For instance, when confronting false preachers with the Scripture, Irenaeus says, “they turn round and accuse these same Scriptures as not being correct, nor of authority, and that they are ambiguous, and that the truth cannot be derived from them by those who are ignorant of tradition.”

However, when confronted with the Tradition — that is, the teaching of the apostles and their successors — “they object to the tradition, saying that they themselves are wiser not merely than the presbyters, but even than the apostles, because they have discovered the unadulterated truth.” This, for Irenaeus, is simply the mark of heretical belief — constantly shifting reasons “that these men do now consent neither to Scripture nor to tradition” (Against Heresies, No. 3.2.1-2). When, neither Scripture nor apostolic tradition is accepted in matters of belief, the Faith is lost through the incoherent whims of innumerable charlatan preachers who twist texts or claim new truths. Detached from the Church, ignorant of tradition, the Scripture is dangerous and bound to be misused, Irenaeus seems to say.

In St. Irenaeus’ writings, we have a picture of an early era of the Church in which in a rather crowded marketplace of competing Christianities — some more fantastic and some more plausible — it’s clear that to embrace authentic Christianity, one must belong to the Church. One must accept the apostolic writings and the traditional view that certain sacred texts are properly interpreted by and preserved by the succession of bishops and presbyters in the Church. The truth of the Scripture is always mediated by the Church, guaranteed over time by the succession of the apostles, the Tradition and the communion of believers enduring through the centuries. “The Church alone understands Scripture,” wrote Henri de Lubac (“History and Spirit,” Page 347). That’s a bold claim. But, put simply, it just means that in one’s search for the authentic Christian faith, one can’t abstract theological truth from the community founded by Christ on the apostles. The Scripture and the Church always go together, which is why we insist that the Church is necessary for a right reading of Scripture.

It goes back to the understanding we began with, which is that when we encounter the word of God, something more than academic is going on. Rather, something spiritual is going on — a mystical experience, an ecclesial experience. God remains involved in the event of encountering the word of God; therefore, so does the Church. As Jesus said in John’s Gospel: “I have much more to tell you, but you cannot bear it now. But when he comes, the Spirit of truth, he will guide you to all truth” (Jn 16:12-13). Jesus himself promised that the Spirit would be present among his disciples and that the job of the Spirit is to lead the disciples into “all truth.” So, in our post-Resurrection dealing with the Gospel, its oral and scriptural transmission and interpretation are still involved with God, sharing in the same Spirit in which the texts were written (cf. Dei Verbum, No. 12).

This is why an authentic encounter with the Scripture is always ecclesial and is always connected to the Church enlivened by the Holy Spirit. Not just as Irenaeus said, but Peter too. “Know this first of all,” Peter wrote, “that there is no prophecy of scripture that is a matter of personal interpretation, for no prophecy ever came through human will; but rather human beings moved by the Holy Spirit spoke under the influence of God” (2 Pt 1:20-21). That is, the transmission of the Gospel, the reading and proclamation of the word of God, and the interpretation of the word of God, is not just a man-made event. When the truth is preached, God is involved. God is the originator of the transmission of the Gospel and its interpretation. It’s not just a matter of human ingenuity. God remains involved. Truth is the first cause, so to speak, of the Scripture and its interpretation. But it’s never detached from the Church — never from the Tradition. This is what Catholics believe: that the Scripture and the Church always belong together.

Father Joshua J. Whitfield is pastor of St. Rita Catholic Community in Dallas and author of “The Crisis of Bad Preaching” (Ave Maria Press, $17.95) and other books. Read more from the series here.