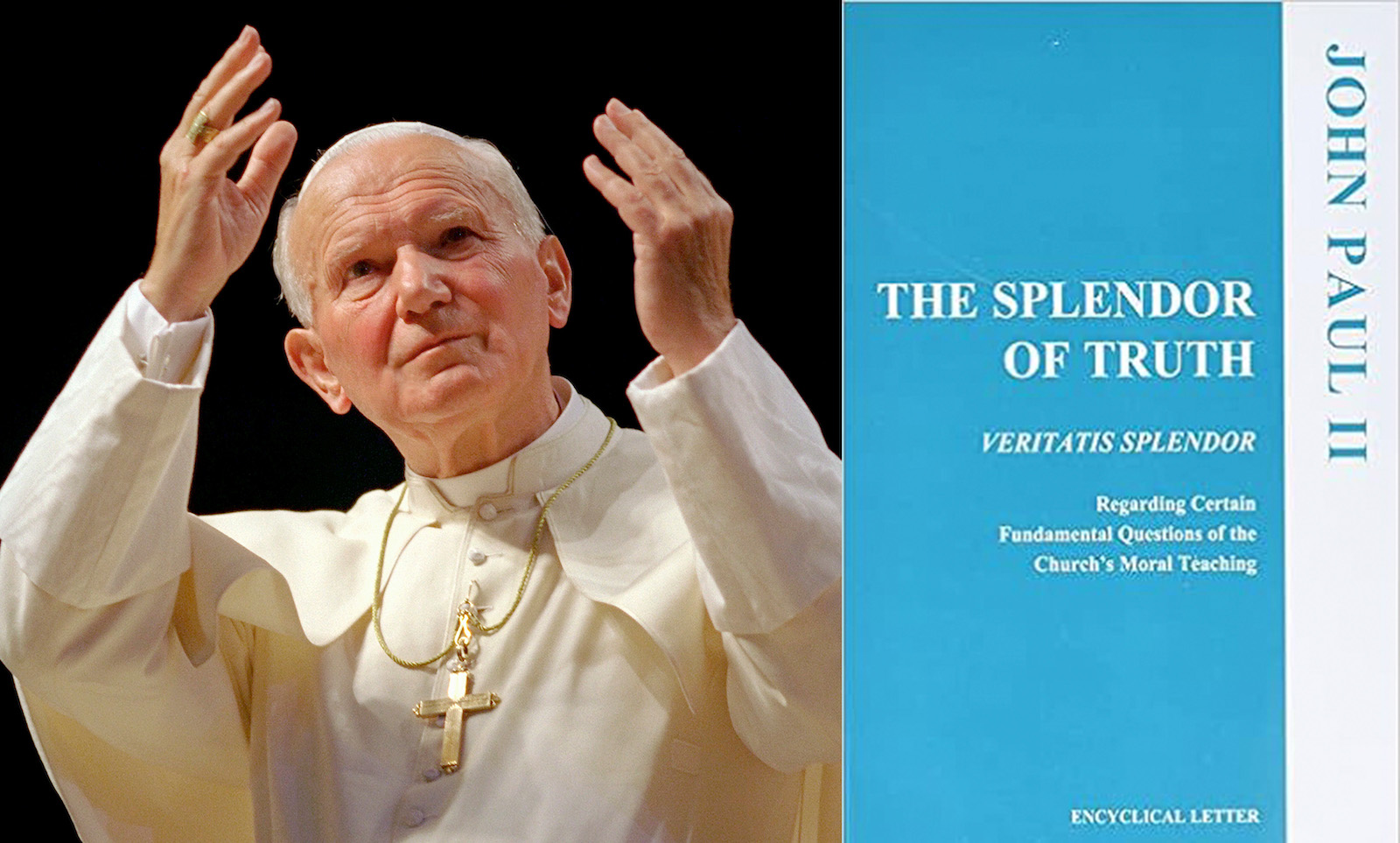

Pope St. John XXIII said we “must” learn it. Pope St. John Paul II said that it should be a part of the “general catechesis” for everyone.

Pope Benedict XVI wrote that it is of “fundamental importance,” necessary for the proper preparation of all the laity. And yet the vast majority of Catholics are either unaware of it or very confused about it.

The “it” is the social doctrine of the Catholic Church.

Like the Second Vatican Council, confusion about social doctrine of the Church often arises because a false “spirit” of social justice is passed off as doctrine when it has little resemblance to the actual teaching. For example, one popular social-justice program never includes a unit on abortion, which is mentioned several times throughout the social teaching, but includes several units on absolute pacifism, though this position does not reflect the doctrinal documents.

What is the Social Doctrine?

The Catechism of the Catholic Church (Nos. 2419 and following) states that social doctrine is a body of teaching that began as a response to the revolutions of the 19th century. Pope Leo XIII wrote the encyclical Rerum Novarum (on capitol and labor) in 1891, inaugurating Catholic social doctrine. Recognizing the importance of Pope Leo’s work, in 1931 Pope Pius XI wrote Quadragesimo Anno (“In the 40th Year,” recognizing the anniversery of Pope Leo’s landmark document) in which he coined the term “social justice.”

Pope Pius XII, his successor, would not write a document on the matter, but did address the teaching in radio messages and various speeches. St. John XXIII contributed two documents in his short reign: Mater et Magistra (on Christianity and the social progress) and Pacem in Terris (“Peace on Earth”). The Second Vatican Council offers us Gaudium et Spes (Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World) and Dignitatis Humanae(Declaration on Religious Freedom) on the subject.

Pope St. Paul VI did a lot to develop the teaching with Populorum Progressio (on the development of peoples) in 1967; Octogesima Adveniens (on the 80th anniversary of Pope Leo’s document) in 1971, in which he rejected Marxist/socialist influences on the social doctrine; and Evangelii Nuntiandi (on evangelization in the modern world) in 1975.

St. John Paul II provided Laborem Exercens, which included a beautiful reflection on the spirituality of labor, Solicitudo Rei Socialis (on the 20th anniversary of Populorum Progressio) and Centesimus Annus (on the one hundredth anniversary of Pope Leo’s first document on social doctrine). Pope Benedict XVI seemingly could not get away from the subject. The second half of Deus Caritas Est (“God Is Love”) discusses it; it appears in Spe Salvi (“Saved in Hope”) several times; and the entirety of Caritas in Veritate (“Charity in Truth”) is a massive contribution to the development of this doctrine.

Five Key Principles

In 2005, the Church’s Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace published the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, which provides concrete principles and values to help explain the teaching. The values necessary for understanding the Church’s social doctrine are truth, freedom, justice and love. In addition, the Compendium provides five principles which build off each other. They are the common good, the universal destination of goods, subsidiarity, participation and solidarity.

Though not exhaustive of all that has been written by the popes or other bodies, the above documents are the core of the social doctrine. Thus the first thing to note is that it is a specific body of teaching that can actually be looked up, referenced and taught. Like the rest of the Church’s doctrine, it is part of an integral whole. It cannot be separated from the rest of Church teaching or cherry-picked to suit a particular party or political movement. In other words, the cafeteria is closed here, too.

Concretely, the Church’s social documents provide principles for reflection, criteria for judgment and guidance for action. It is a branch of moral theology and so is meant to help us deepen and broaden our personal relationship with Christ. Pope Benedict XVI made this clear in Caritas in Veritate, when he teaches that charity unfettered from the authentic truth of the dignity of the human person becomes hollow sentiment or, worse, can cause harm. Rather, the fullness of human dignity is realized only with the Word who was with God at the beginning. Unity with Christ is necessary to authentic social justice, for He is Truth with a human face.

An Invitation

Catholic social doctrine, then, becomes an invitation to deepen our relationship to Christ so that He leads our social-justice activity. Quoting St. Paul, Pope Benedict said that it is the love of Christ which urges us on to action — and what a love it is! In the divine Jesus, crucified for us, we discover a God who loves us even unto self-emptying death.

It is this astounding love that Jesus commands us to have for one another and that only He can provide us by grace. This grace promotes an authentic liberation from a personal sinfulness that keeps us from serving those most in need. Liberation theology, a popular brand of social thought founded in the 1970s, has caused some of the confusion around social justice. It tends to focus on liberation from socioeconomic burdens and ignores personal sin or salvation.

Guided by Marxist thought, it emphasizes political restructuring to solve social ills. Unfortunately, some liberation theologians become all too comfortable with denying Christ’s divinity as they feel it is ultimately unimportant to social reform and class upheaval. In some writings of liberation theology, the Crucifixion ceases to be about the salvation of humankind from sin and becomes only another example of what happens to those who preach political and social revolution. Our Lord becomes a radical community organizer and ceases to be the Word who became flesh.

Authentic Catholic social doctrine rejects socialism and embraces efforts for justice and peace that begin with personal conversion to Jesus. It must be rooted in a love infused by divine grace that cannot help but spill out into uninhibited care for our neighbors. And, in this way, social doctrine can become an integral aspect of our spiritual lives.

So, for instance, according to Gaudium et Spes, the common good is the sum total of social conditions that allow people to reach their fulfillment more fully and more easily. “Total human fulfillment” for the Catholic can be nothing less than personal sanctity. Who are better examples of human fullness and of a love for the poor and marginalized than our Catholic saints, after all?

Therefore, instead of being an argument for the socialist collective, pursuit of the common good is the pursuit of those social conditions that support the universal call to holiness. Pursuit of the kingdom of God is pursuit of life in Christ, is pursuit of social justice. This is the social teaching of the Catholic Church. This is why, at the end of Caritas in Veritate, Pope Benedict told us that the development of a just society requires “Christians with their arms raised towards God in prayer.” It starts with Christ and ends with Christ in the homeless, the lonely and the destitute.

Omar F.A. Gutiérrez writes from Nebraska.

Living Social Doctrine

Given the “fundamental importance” of the Church’s social doctrine, the general confusion and ignorance about it could tempt one to despair. However, as St. John Paul II once pointed out, Catholic social doctrine is really not new. It places the family at the heart of society, which is a very ancient idea. The Church prioritizes social-justice activity starting with family and proceeding to culture, to economics and to politics, in that order. In other words, one can be engaged in social justice by spending time at a soup kitchen and by changing a diaper.

Social doctrine is protesting the pornography shops and turning off the television when it corrupts the heart. It is working in favor of immigration reform and inviting the new family on the block for dinner. It is loving God and always loving your spouse while being open to life. A family founded on prayer, the sacraments and the pursuit of holiness can do more for social change than anyone’s grand plans for social revolution.

A holy family can also be the most accessible and persuasive Gospel of all, and is the primary school for living out the social doctrine.

One finds, then, that authentically living out Christ’s good news for the poor is often the most eloquent argument for the faith. The evangelical nature of Catholic social doctrine is specifically mentioned by St. Paul VI and Pope Benedict XVI, and many have been converted to Catholicism because of this social doctrine.

For those gray areas of life that befuddle, Catholic social doctrine is there as a light in the darkness by which we can live by Christian values and principles, and so we ought to reclaim it.