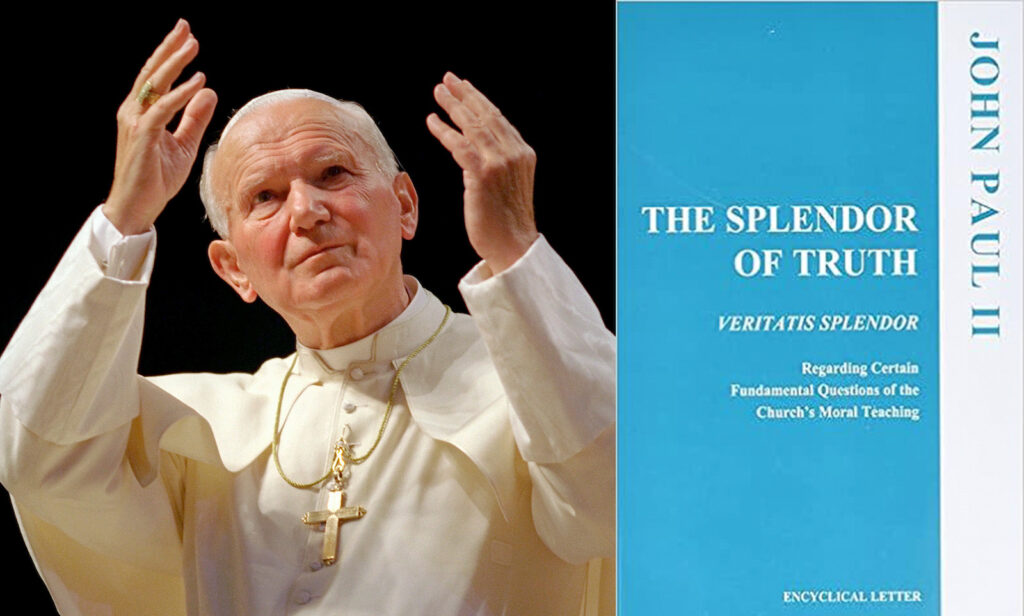

Aug. 6 marks the 30th anniversary of Pope St. John Paul II’s encyclical Veritatis Splendor (”The Splendor of Truth”). It is the first and only papal encyclical focused on moral theology. Its continued importance cannot be underestimated, even while its teachings are often overlooked or even ignored.

It is a rather dense document, making for difficult reading at times. But it is also very direct in addressing postconciliar confusion about foundational truths regarding morality, freedom and conscience. Here are four essential truths the pope taught through the encyclical.

1. Man can know the truth. Truth makes man what he is. We are called to know truth; it is truth that sets us free.

The opening lines of the encyclical state: “The splendor of truth shines forth in all the works of the Creator and, in a special way, in man, created in the image and likeness of God (cf. Gn 1:26). Truth enlightens man’s intelligence and shapes his freedom, leading him to know and love the Lord” (Veritatis Splendor, No. 1).

This is a summary of what we call “natural law.” As St. John Paul states a bit later in the document, “Only God can answer the question about the good, because he is the Good. But God has already given an answer to this question: He did so by creating man and ordering him with wisdom and love to his final end, through the law which is inscribed in his heart (cf. Rom 2:15), the ‘natural law’” (Veritatis Splendor, No. 12).

Truth is what is real. To grasp truth is to see things and relationships as they are, through use of reason and correct judgment. Contrary to the relativistic and even fatalistic views popular today, we are created in truth and for truth.

2. Christ is the true light: St. John Paul begins by reflecting on original sin. We are tempted to turn away from God and toward idols. “Man’s capacity to know the truth is also darkened, and his will to submit to it is weakened” (Veritatis Splendor, No. 1).

The solution to that darkness is “Jesus Christ, the true light that enlightens everyone,” he writes. “The “decisive answer” to all of our questions “is given by Jesus Christ, or rather is Jesus Christ himself.”

St. John Paul then focuses on Christ’s statement: “You will know the truth, and the truth will make you free,” words that contain “both a fundamental requirement and a warning.” We must avoid false and superficial “freedoms”; we need, as St. John Paul wrote earlier in Redemptor Hominis (”Redeemer of Man”) to “see Christ as the one who brings man freedom based on truth, frees man from what curtails, diminishes and, as it were, breaks off this freedom at its root, in man’s soul, his heart and his conscience” (Redemptor Hominis, No. 35).

The first major section of Veritatis Splendor is focused on the dialogue of Jesus with the rich young man (cf. Mt 19). Which brings us to the third truth.

3. True freedom is freedom for the good. John Paul II notes that for the rich young man, “the question is not so much about rules to be followed, but about the full meaning of life.” Which is why Jesus responded: “Why do you ask me about what is good? There is only one who is good” (Veritatis Splendor, No. 6).

If we are honest, we recognize our desire for Something or Someone beyond ourselves. The transitory things of this world cannot satisfy us. We long for what is good: “Only God can answer the question about what is good, because he is the Good itself. To ask about the good, in fact, ultimately means to turn towards God, the fullness of goodness” (Veritatis Splendor, No. 9).

But if God alone is the Good, our natural human efforts, including keeping the commandments, cannot fulfill the Law. “The essence of legalism is the conviction that doing the right things will suffice.” What must be done? We must participate in the very life of God, by his grace and mercy, in order to attain the beatitude and happiness we desire (cf. Veritatis Splendor, Nos. 12 and 41).

Many people mistake “freedom” with individual autonomy. But true freedom is not given so man can do whatever he pleases, but so he can choose the good. “Genuine freedom is an outstanding manifestation of the divine image in man” (Veritatis Splendor, No. 34).

In sum, true freedom is freedom for the good. In this true freedom, we find our real dignity. “Freedom then,” writes St. John Paul, “is rooted in the truth about man, and it is ultimately directed towards communion” (Veritatis Splendor, No. 86).

4. One’s conscience judges an act. It does not determine moral truth. “Conscience” is a key word in Veritatis Splendor, appearing 108 times. St. John Paul knew that many people erroneously think their conscience is the final guide to what is truth and good. “The individual conscience is accorded the status of a supreme tribunal of moral judgment,” he writes, “which hands down categorical and infallible decisions about good and evil” (Veritatis Splendor, No. 32).

He notes that some people set aside truth and replace it with “a criterion of sincerity, authenticity and ‘being at peace with oneself,’” which can lead to “a radically subjectivistic conception of moral judgment.”

Ironically, those claiming they have attained “truth” by appealing to their conscience actually deny the existence of a universal, objective truth. The problem worsens when they construct a morality based on whims divorced from universal truth. The conscience is given “the prerogative of independently determining the criteria of good and evil and then acting accordingly.” This reflects “an individualist ethic, wherein each individual is faced with his own truth, different from the truth of others” (Veritatis Splendor, No. 32).

Ultimately, this leads to a denial of “the very idea of human nature.” There are two ways of approaching reality: trying to create our own reality, which is destructive, or conforming ourselves to reality — to what really is.

And, importantly, one’s conscience can be wrong! “Conscience, as the judgment of an act, is not exempt from the possibility of error” (Veritatis Splendor, No. 62). The conscience cannot create moral truth; rather, it makes an informed judgment about actions, based on what is true and morally right, because conscience “is a moral judgment about man and his actions, a judgment either of acquittal or of condemnation, according as human acts are in conformity or not with the law of God written on the heart” (Veritatis Splendor, No. 59).

In 1998, then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger described Veritatis Splendor as “a milestone in the elaboration of the moral message of Christianity” while noting that it had “more positive receptions among thinkers outside the Church than among some exponents of Catholic theology.”

The situation remains much the same today. Truths about man, Christ, freedom and conscience still require clear explanations and consistent applications. This great encyclical has yet to be studied, assimilated and applied as deeply as it should be.

Carl E. Olson is editor of Catholic World Report and Ignatius Insight and the author of several books. Follow him on Twitter @carleolson.