Some years ago a noted scientific journal published an article on the geometry of humor.

The author pointed out that all humor follows a certain geometric pattern, which was both described in a mathematical formula and illustrated as a triangle. A joke, a riddle, a pun all conceptually lead a person up an incline and give the impression that the incline will continue, but with the punch line the path drops off like a cliff. In listening to or reading a joke, or in contemplating a riddle, a person’s mind begins to project where the story line is headed, but the surprise trajectory — an unexpected and rather sudden change in direction — is what causes the reaction: laughter.

Parables

There’s something sterile about describing humor in a mathematical formula, even if one might find the effort humorous in itself. Even so, it seems that the parables of Jesus follow the same geometry: presenting a scenario, leading the listener to project an ending, then suddenly delivering a punch line that surprises or shocks. Several authors have suggested that those who first heard Jesus’ parables in first-century Palestine might actually have found them humorous, in part because of the surprise endings, but mostly because of the fanciful or unusual situations Jesus depicted. The master parable teller painted a story with familiar details that may have led the hearers to look forward to a predictable ending, only to see the story’s trajectory changed to an unforeseeable conclusion.

As soon as you recognize that a joke is in the works, you know you’re no longer on safe ground. The punch line could come at any moment: a twist, a surprise, a play on words. In the telling of a joke, everything changes for a moment. Assumptions aren’t safe. The familiar becomes unfamiliar. The listeners are anxiously expecting the surprise at the end.

It’s difficult to imagine anything that comes closer to an encounter with the Jesus of the Gospel.

Humor, however, has not always been a laughing matter in the history of the Church.

Although Ecclesiastes 3:4 tells us that there is “a time to weep, and a time to laugh,” and although Sarah famously laughed when angelic visitors told her husband Abraham that she would bear a son within the year, most biblical references to laughter do not bring a smile to the face. When the Bible refers to laughter it is often the scornful laughter of a sinner reviling God, or — since God gets the last laugh — the response of God to such scorn.

Similarly, the Church Fathers give short shrift to laughter, seeing an incongruity between the awareness of one’s sins and the willingness to laugh. St. John Chrysostom, one of the dour Fathers, suggests that weeping is preferable to laughing in this vale of tears.

Yet the shared experience of every human is one of both weeping and laughing, of mourning and of dancing. The author of Proverbs reminds us that laughter and sadness abide together, one never far from the other. Together with the pain of separation from God, humanity’s experience of God is replete with joy: the delight of Adam discovering Eve; the unbounded glee of King David dancing before the Ark of the Covenant; the happy leap of John the Baptist in the womb; heaven’s elation at one repentant sinner; and, ultimately, the words we all long to hear, “Come, share your master’s joy” in heaven, where “there shall be no more death or mourning, wailing or pain” (Rv 21:4). A walk through the Bible shows that references to joy far outweigh the mention of sadness.

Part of God’s Love

Without disagreeing that our sins are cause for sadness and repentance, serious Christian thinkers such as Søren Kierkegaard and Reinhold Neibuhr suggested that the ability to laugh at ourselves and at the foibles of the world is both a prelude and a result of true contrition for our sins. The influential 20th-century theologian Father Karl Rahner saw laughter as a gift from God, a tutor to help us understand God’s love for us. Humor helps to keep us humble, recognizing and admitting our imperfections before God.

G.K. Chesterton, a prolific essayist and author of fiction, biography, poetry and plays, finally converted to Catholicism in 1922 after his faith grew in a lengthy germination. He valued humor as a sign of wonder, and wonder as a doorway of spirituality. No reader of Chesterton’s essays can come away without a smile and perhaps a hearty laugh. And no one can doubt his faith in God’s goodness. Another convert to Catholicism late in life, Malcolm Muggeridge, saw humor as God’s therapy and looked forward to hearing “the unmistakable sound of celestial laughter” in heaven.

Joy and laughter are part of our heritage as children of God, just as they are part of our experience as human beings. Together with weeping and sadness they frame our experience of life.

Though the Gospel writers note the tears of Jesus as He wept over Jerusalem, at the tomb of His friend Lazarus and certainly in Gethsemane’s garden, no one can doubt the joy which permeated Jesus’ public ministry. It’s impossible not to picture Jesus and His apostles as joyful at the wedding feast in Cana. Joyful feasting was a common image of the Lord in His parables.

Indeed, in His priestly prayer in John’s Gospel, the Lord is clear about His mission: “That my joy might be in you and your joy might be complete” (Jn 15:11).

Joy Is First

St. Paul reminds the Galatians that joy is one of the fruits of the Holy Spirit, a sign and symptom of a life lived in the Spirit of God. He also gives us an instruction toward the end of his First Letter to the Thessalonians, a practical lesson for how to live in a world that is passing away. After urging the Christians in Thessalonica to “cheer the fainthearted” who worry unduly about the final judgment, he gives a three-part instruction for life: “Rejoice always. Pray without ceasing. In all circumstances give thanks” (5:16-18).

Notice, joy is first.

The ability to find joy in all circumstances — to laugh at the vicissitudes of life knowing that God has conquered all in Christ Jesus — is indeed a sign and symptom of sanctity. The saints show us this.

St. Lawrence, deacon of the church of Rome, was arrested three days after the seizure and martyrdom of his bishop, Pope St. Sixtus. When the pagan prefect of Rome demanded that Lawrence, who as a deacon was responsible for providing aid to the poor and needy, produce the hidden wealth of the Church, Lawrence asked for three days to assemble it. At the appointed hour he gathered the poorest and neediest persons from around the city and told the prefect, “This is the Church’s treasure.” The prefect saw no humor in that and ordered Lawrence be tied to an iron grill and burnt slowly over a fire. God gave Lawrence the gift of humor in the midst of his torture, such that he is said to have joked with his torturers, “Turn me over, I’m done on this side.”

The humor of Teresa of Jesus, the Spanish Carmelite reformer from Ávila, is well known. Among the quotes attributed to her is a smiling retort to God when the saintly nun was thrown off a cart into a mud puddle as she traveled to visit a monastery. Looking up from the muddy road, Teresa said to God, “If this is how You treat Your friends, no wonder You have so few!” St. Teresa is also said to have given the following advice to a young novice who admitted falling asleep every day at prayer: “If you go to prayer and find yourself falling asleep, accept it as a gift from God. If, however, you fall asleep at prayer every day, find another time to pray.”

Indeed, it may be the deep holiness of St. Teresa that allowed her to maintain a sense of humor even in the midst of turmoil. Only one with a deep and passionate trust in God’s goodness could seek and treasure humor in the midst of travails and disappointments such as Teresa experienced. She wrote: “Let nothing trouble you, let nothing frighten you. All things are passing; God never changes. Patience obtains all things. He who possesses God lacks nothing: God alone suffices.” Such confidence buoys the soul and produces a light heart. It is the truest font of joy and humor for the believer.

Why is humor important? Principally because it keeps us from taking ourselves too seriously. If we recognize that here on earth we have not a lasting city, it’s perhaps best to laugh at the incongruities while joyfully accepting God’s grace to act as agents of His redemption. In other words, perhaps a believer’s best attitude in life is to change what we can change and laugh at what we cannot, completely confident that God has already bested whatever tries to keep us from joy.

Msgr. William King is a priest for the Diocese of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

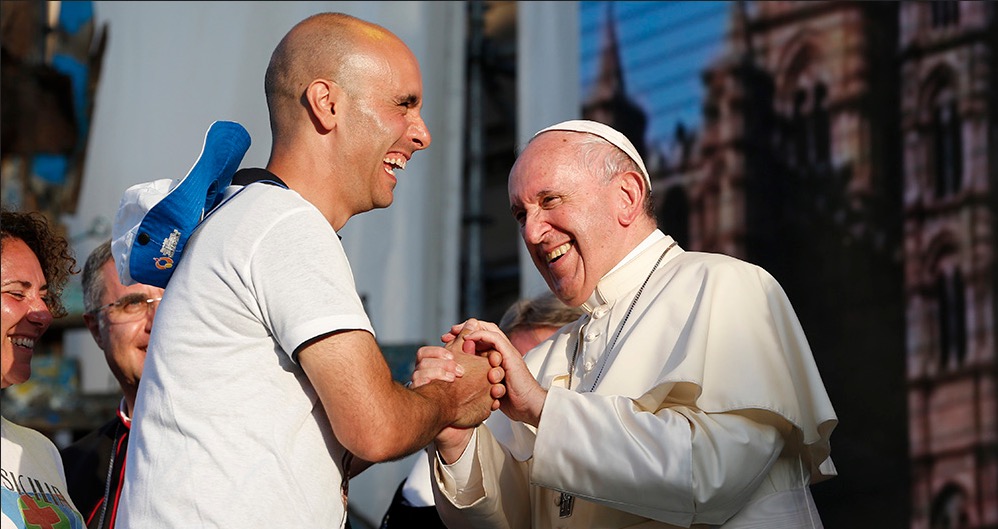

Pope Francis on Joy

“Instead of imposing new obligations, [Christians] should appear as people who wish to share their joy, who point to a horizon of beauty and who invite others to a delicious banquet.”

“Be courageous in suffering and remember that after the Lord will come; after, joy will come, after the dark comes the sun. May the Lord give us all this joy in hope.”

“Christianity spreads through the joy of disciples who know that they are loved and saved.”