Jesus, “though he was in the form of God, / did not regard equality with God something to be grasped. / Rather, he emptied himself, / taking the form of…

Jesus, “though he was in the form of God, / did not regard equality with God something to be grasped. / Rather, he emptied himself, / taking the form of a slave, / coming in human likeness; / and found human in appearance, / he humbled himself, / becoming obedient to death, / even death on a cross” (Phil 2:6-8).

This Scripture passage from St. Paul summarizes the humility of Jesus Christ and his self-emptying, also called kenosis in Greek.

The question of Christ’s self-emptying is very urgent today as there are many who question the traditional doctrine taught by the Council of Chalcedon (A.D. 451) concerning the nature of Christ. This applies even to professional teachers of theology, who sometimes teach that Jesus is just a good man who is engraced in the same way any other human being is and therefore is an adopted, not a natural, son of God. There are two basic clarifications which must guide any truly Catholic understanding of Christ. The first concerns what the union of God and man is in Christ. The second concerns how the first doctrine is reflected in certain actions of Christ — for instance, His cry, “My God, My God why have you forsaken me?” from the cross (see Mt 27:46).

God and Man

When God became man in the Christ, this was a true self-emptying in humility. But what was exactly given up? Did Jesus cease to be God? What did He assume? Where does the union of God and man take place?

The attempt to explain this belief puzzled the early Christians. They used terms taken from Greek philosophy to attempt to explain the mystery in which they believed. Not that they could exhaust this mystery. That is not possible as it is a part of the ineffable wisdom of God. But since this mystery is received in a human mind, the early Christians used philosophy as a tool to help clarify what they actually believed in. The principle terms they used were: person, nature and relation.

In Greek philosophy a nature is a principle of a kind of activity which sets one being off from another. The way a dog acts differs from a tree. This demonstrates that a dog has certain powers different than a tree and so is a different being, possessing a different nature. The individual who possesses a nature which is shared by all the individuals of its species is called a hypostasis. An individual who possesses a rational nature (a hypostasis with a rational nature) is a person.

Once the divinity of the Word was determined, the question arose as to how the Word was present in Jesus of Nazareth. Many attempted to explain this by saying that God and man were united in nature in Christ. This did not do justice to what Christians believed or the Christ to whom they prayed. If the union took place in nature, Jesus would have to be really God and only seem to be man, really man or seem to be God, or be a strange monstrous mixture of the two. The heresy which teaches that the union takes place in the natures is Monophysitism, which derives from the Greek words mono(one) and phusis (nature). This would mean that Christ would, in some sense, be just a good man somehow identified with God, or only seem to be man.

Instead, the Council of Chalcedon taught that the union takes place in the person. The divine person of the Word who shares the divine nature with the other two persons, at a certain point in time, took unto himself a new way of acting, a human nature, but not a human person. God was not changed by this action, but the world was. What had been called to union with God in nature by a quality of being called sanctifying grace became a new and unheard of relation, and the world was united to God in the person of the Word. The union in person is thus called “the hypostatic union,” which is a grace unique to Christ. Christ does not assume a human person, but only a human nature, a perfect and complete one nonetheless. He has a human soul, intellect, will, passions and body.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church recounts for us the definition from Chalcedon: “We confess that one and the same Christ, Lord, and only-begotten Son, is to be acknowledged in two natures without confusion, change, division, or separation. The distinction between the natures was never abolished by their union, but rather the character proper to each of the two natures was preserved as they came together in one person (prosopon) and one hypostasis” (No. 467).

This means that the emptying of Christ in being consisted in His will to join human nature to His actions as a divine person, to act through it and to only hide the glory of His divine nature so that He might suffer the passion: “What he was, he remained; what he was not, he assumed” (Catechism, No. 469).

The one divine person, Jesus, thus acts in two natures. In Scripture, He even demonstrates this because He speaks in both natures as one person often in the same verse. “Now glorify me [human nature], Father, with you, with the glory that I [divine nature] had with you before the world began” (Jn 17:5). This new relation between God and the world is a sheer grace, and it is also a miracle.

St. Paul’s Letter to the Philippians continues the passage about the nature of the self-emptying: “God greatly exalted him” (2:9). Does this mean Christ was not exalted in being before the Passion? Often, things are said to occur in Scripture when they come to our knowledge. Before the Passion, Christ rarely demonstrated His divinity. But after the Passion, in the Resurrection and the Ascension, His divinity becomes clearly demonstrated to the apostles. They come to know it.

What Did He Give Up?

One of the difficulties with this position is how one can dogmatically explain the cry of Christ from the cross: “My God, my God, why have your forsaken me?” Many theologians today hold that Jesus was forsaken because He had no idea He would rise from the dead, that He threw himself into a kind of existential darkness characterized by faith and just accepted the meaninglessness of life. So, His experience of death would be the same as ours.

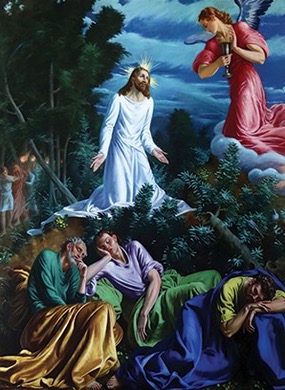

Agony in the Garden, altar painting in the Church of St. Vitale, Parma, Italy. Zvonimir Atletic/Shutterstock.com

This is impossible. In what sense can Christ be forsaken on the cross? He cannot cease being the Word of God within the Trinity. This is His personhood. He cannot cease being the Word made flesh. This union is permanent once embraced. He cannot sin as this would war against His mission, which is to atone for our sins by His perfect obedience on the cross.

The traditional teaching of the Church is that Christ enjoys the beatific vision from the moment of His conception in the womb of His mother in His human intellect. This is not formally defined de fide, but has always been considered proxima fide, meaning that to deny it entails so many problems for other doctrines that it must be affirmed. If Christ were not to have this and therefore have faith on the cross, this would mean that He would have to merit it for himself as man and, in principle, could sin. In fact, faith is never attributed to Christ in His earthly life, and the ability to sin would again compromise His mission.

The only way Christ can be abandoned by His Father on the cross, then, is by external protection. Many times Christ’s enemies sought to put Him to death, beginning with Herod, when Christ was a baby, and God protected Him. The dogmatic difficulty here is resolved if one considers that “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” is the opening verse of Psalm 22 (RSVCE). If one reads the whole psalm, it is very far from a cry of despair and existential angst. The psalmist does suffer intensely, but the psalm ends with a hymn of thanksgiving to God and confidence that God will vindicate his sufferings. This will, of course, happen in the resurrection of the dead. Moreover, Thomas Aquinas thought that no one could freely give himself to the kind of suffering Christ embraced on the cross unless he knew about the resurrection of the dead.

The self-emptying of Jesus then is only a self-emptying in being in the sense that God should choose to take to himself a human way of acting and suffering. Psychologically this emptying does not involve sin. It is not even done in faith.

Rather, in this suffering Christ experiences the greatest pain possible. This is the case physically because His body was more sensitive than a normal body as it was perfectly fashioned by the Holy Spirit. He therefore suffers more in the bruises, the scourging, the nails and the hunger and thirst.

He also suffers mentally because he personally experiences all the human sins which will be committed and have been committed in the history of the human race. He knows these through the beatific vision He has on the cross. He does not allow this vision, or His glory as God, to enter into His lower self precisely so He can suffer the Passion. He feels abandoned by God, but knows internally He is not. This is a cause of acute pain both physically and mentally. But the internal union of the hypostatic union is preserved.

So, in Jesus, we see how much God loves us. We should therefore be caught up in love of the God we cannot see (see Roman Missal, Christmas Preface).

Father Brian Mullady, O.P., S.T.D., earned his doctorate in Sacred Theology from the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas in Rome.