Today health care is described as many things, including a profession, business, industry or even a right. However, long before health care was any of these things, it started as a calling to serve by caring for those who are ill.

The word “vocation” comes from the Latin word vocare, which means “to call.” While all of us are called to holiness and a specific state in life — such as married or religious — some, too, have a vocation to a specific type of service for their daily work. A vocation to care for the sick was the genesis of health care and should serve as the cornerstone in a discussion regarding any aspirations for health care in general and for health care workers in particular.

Spurred by Christianity

While some roots of modern medicine can be traced back to Hippocrates’ Oath, health care as we know it today largely developed thanks to Christianity. Prior to the time of Christ, there were no hospitals to speak of, and health care was largely utilized to keep soldiers and slaves in working order. The general public who became ill were ostracized and begged in the streets.

Christ, however, changed this paradigm by his example. In his public ministry, he used the healing of the sick to spread the Good News of God’s love and forgiveness. In many New Testament stories, upon arriving in a new town, he would heal the sick prior to preaching to the crowds. No doubt many of those who heard his message of hope were first drawn to him by his works to alleviate the suffering of the ill. Prior to Christianity, health care was considered from the point of utility — to keep people on the job. But Christ’s example and teachings led to a new understanding that caring for the sick was a holy endeavor, in and of itself, because each human person was created in the image of God.

Christ taught in Matthew 25 that “whatever you did for one of these least brothers of mine, you did for me.” It is this charge that served as a spiritual calling for the many holy men and women who built hospitals, studied disease and developed treatments and surgeries to care for the sick among us, leading to the growth of health care as we know it today. Without Christ’s teachings and example, it is quite likely that many positive aspects of health care as we know it would not have come to be. Charitable care for the indigent, and even the ubiquitous nature of health care services in general, can be traced back to a dedication driven by a calling in the lives of many pioneers in health care from the likes of St. Camillus, to St. Mother Teresa, to Servant of God Jerome Lejeune and countless others who dedicated their whole lives to caring for the sick.

Health care is vocation

The importance of the vocational nature of health care is highlighted by its absence today in places where it is being forgotten. If health care is a business rather than a vocation, profits will guide care choices, and patients will suffer. If health care is an industry, then it is something that is to be regulated for the benefit of the state, and health care workers will suffer. We unfortunately see this today by infringements on the conscience rights of health care workers today when they are coerced to act against their deeply held beliefs. If health care is something to be demanded from those providing it, both patients and health care workers can suffer and the good of both can be misplaced.

This is an all too common misconception that can, in essence, indenture health care workers by disregarding their rights as workers rather than creating a mutual and fiduciary relationship between doctor and patient. In part, this has led hospitals and health care workers to be mere dispensaries of services, even if it is not in the best interest of the patient. The fruits of this tree can be seen most saliently with what has happened with the opioid crisis in recent years. While health care has aspects of each of these things, if we lose the centrality of health care as a vocation, then we jeopardize the many wonderful things that have been achieved by those who preceded us.

In contrast, when properly regarded as a vocation, health care can be a blessing to the called and to those whom they serve. Additionally, for one who works in health care, it can be a path of holiness as well. On a daily basis, a health care worker has many opportunities to practice corporal and spiritual works of mercy. Frequently, patients who suffer physical ailments share their mental and spiritual burdens as well. This is true especially for patients who do not have a strong faith as these interactions provide occasions for evangelization. Health care workers have the opportunity to show Christ’s love to them in a time of need, not only in caring for the physically ill, but in interacting with people who are frequently in physical or mental distress. It is always my hope that if patients are treated with love, they will recognize that it is because of Christ that we love them.

Health care is in a great need of a resurgence of viewing medicine as a calling in this way. It is for this reason that I always encourage those who are considering this path because it is filled with many joys and blessings for oneself as well as many opportunities to truly touch the lives of those for whom they care. It is these health care workers who will provide the best care for patients because of their dedication to those they serve.

In modern times we are faced with many questions regarding health care. How it is financed? How it is provided? How can we entice more workers to choose health care to improve staffing shortages and access for patients? These are all critical questions as we work to improve the system that we live in. However, if we can keep the focus of health care as a vocation and Christ as our example, we will most certainly make better choices for health care policies that will help both the health care worker and the patient engender a culture of virtue in the process.

Dr. Andrew J. Mullally, MD, is a family physician who co-hosts the “Doctor, Doctor” radio show on EWTN and practices in Indiana.

Co-patrons of nurses and nursing associations |

|---|

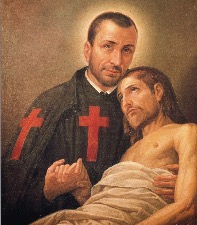

St. Camillus de LellisFeast Day — July 18  Public domain This 16th century Italian saint knew suffering and illness on a personal level. After serving in the army, Camillus contracted a leg disease which prevented him from becoming a Capuchin as he desired. Instead, he used his time to care for the sick and even became the director of the Roman hospital, St. Giacomo. Eventually he was ordained a priest and founded his own congregation, which began by ministering to those at Holy Ghost Hospital in Rome and later extended their work to Naples. In 1591, Pope Gregory XIV granted permission that they become a religious order, and they took the name of the Ministers of the Sick (also known as the Camillians), identifying themselves through a red cross on their cassocks. Soon Camillus sent his brothers to serve the wounded in Hungary and Croatia, becoming the first field medical unit. By the time of his death, the order had over 300 members. St. John of GodFeast Day — March 8  Public domain John’s life was defined by his impulsive nature. At a young age, he ran away from home to follow a visiting priest who spoke about the New World. However, falling sick on their travels, John became a shepherd before fleeing an unwanted marriage to become a soldier in the Spanish army, where he lived a life of sinfulness. John had a change of heart when he was thrown from his horse, and he soon decided to go to African and rescue Christians. However, his heart was moved when he met a noble family being exiled to Africa and offered to be their servant. The family fell ill, and John nursed them back to health. Returning to Spain, John worked as a religious book seller until he heard a sermon by St. John of Avila on repentance, causing John to give up all his belongings. The townspeople thought he had gone mad, so they hospitalized him until St. John of Avila told him his penance was over. From that point onward, he began caring for the sick in the hospital, and he went on to form to treat the poor, forming the Brothers Hospitallers to assist him in his mission. John died from pneumonia after diving into a frozen river to save one of his companions. |