Many Catholics hear that priests are required to recite the Liturgy of the Hours, or the Divine Office, and assume it is a “private” prayer said only by priests and those in religious orders.

Although clerics and religious are obligated by Church law to say the Divine Office (see Canons 1173-1175), laymen and women are increasingly making the Liturgy of the Hours part of their spiritual growth and development by reciting morning and evening prayer. Why are these prayers important in the life of the Church?

“Seven times a day I praise you”

The Divine Office owes its remote origin to the inspiration of God’s Covenant with the Jewish people. He commanded the Aaronic priests (c. 1280 B.C.) to offer a morning and evening sacrifice (see Ex 29:38-39). During the Babylonian Exile (587-521 B.C.), when the Temple did not exist, the synagogue services of Scripture readings, psalms and hymns developed as a substitute for the bloody sacrifices of the Temple, a sacrifice of praise.

The inspiration for this development may have been sentiments in Psalms such as King David’s prayer, “Seven times a day I praise you” (Ps 119:164), and the statement that God’s law is studied by those who are righteous “day and night” (Ps 1:2).

After the people returned to Judea, and the Temple was rebuilt, the prayer services developed in Babylon for the local assemblies (synagogues) of the people were brought into Temple use as well. We know that in addition to morning and evening prayer to accompany the sacrifices there was prayer at the third, sixth and ninth hours of the day.

The Acts of the Apostles notes that Christians continued to pray at these hours (see Acts 2:15; 10:3). And, although the apostles no longer shared in the Temple sacrifices — they had its fulfillment in the “breaking of the bread” (the Eucharist) — they continued to frequent the Temple at the customary hours of prayer (Acts 3:1).

Monastic and eremitical (hermit) practice, as it developed in the early Church, recognized in the psalms the perfect form of prayer and did not try to improve upon it. The practices were quite individual from monastery to monastery. At first some tried to do the entire Psalter (150 psalms) each day, but eventually that was abandoned for a weekly cycle built around certain hours of the day. With the reforms of the Second Vatican Council the traditional one-week Psalter cycle became a four-week cycle.

Among the earliest Psalter cycles of which we have a record is the division given by St. Benedict in his Rule for Monasteries (chapters 8-19) around 550, with canonical hours of lauds (morning prayer) offered at sunrise, prime (first hour of the day), terce (third hour, or midmorning), sext (sixth hour, or midday), none (ninth hour, or midafternoon), vespers (evening prayer) offered at sunset, and compline (night prayer) before going to bed. In addition, the monks arose to read and pray during the night. This Office of Matins (Readings) likewise had its divisions into nocturnes, corresponding to the beginning of each “through the nightwatches” (Ps 63:7) — that is, 9 p.m., midnight and 3 a.m.

After the Council of Trent and its reforms, the Roman Breviary became the Office of the entire Latin Church. It should be noted that religious orders have a right to their own version, though many simply use the Roman Office. These versions are typically used by members of monastic and contemplative communities, such as the Trappists and Carmelites.

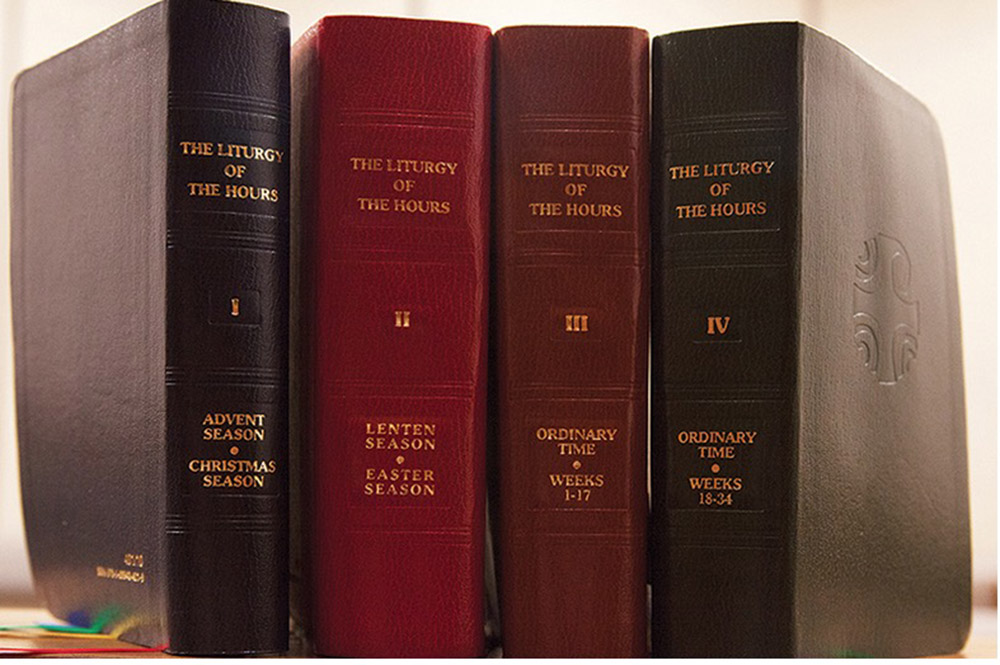

The name Liturgy of the Hours was adopted in 1970 to emphasize that the purpose of prayer was to sanctify the whole day and every activity of daily life in the modern world. Pope Paul VI, in his apostolic constitution Laudis Canticum establishing the Liturgy of the Hours, wrote, “Since the Liturgy of the Hours is the means of sanctifying the day, the order of this prayer was revised so that the canonical hours could more easily relate to the chronological hours of the day in the circumstances of modern life.”

The Liturgy of the Hours is organized currently in a similar way to the earlier Divine Office, but with a number of significant changes. Lauds (morning prayer) and vespers (evening prayer) are given a clear priority, with the rest of the day structured around them. A midday prayer is suggested — shorter than morning and evening prayer. Communities of contemplatives are still required to observe all three (and others are encouraged to do so), but one may choose to use only one, with the texts that are offered. Compline (night prayer) is retained, with the change that it could now be recited after midnight (previously, it was necessary to complete the entire cycle before midnight). A major addition was the Office of Readings.

Praying With One Accord

Public and common prayer by God’s holy people is rightly considered to be among the most important duties of the entire Church. We see how from the very beginning those who were baptized “devoted themselves to the teaching of the apostles and to the communal life, and to the breaking of the bread and to the prayers” (Acts 2:42). As one continues reading the Acts of the Apostles, frequent testimony is given to the fact that the entire Christian community prayed “with one accord” (Acts 1:14; 4:24). When the Christian faithful pray the Liturgy of the Hours, they are connected in a very real and unique way to others who are praying this form of liturgical prayer, so that indeed from the rising of the sun to its setting we proclaim the glory and honor of God.

Prayer is classically defined as lifting our hearts and minds to God. When the Liturgy of the Hours is celebrated, the people of God are not only united with the Church in prayer, they are praying words blessed by Him that reflect the full spectrum of our human experience and that call for the sanctification and healing of our world.

Derek Abrajano writes from Chicago.