In every day and age there have been certain cultural norms that are accepted and followed without much questioning.

For instance, when eating out at a restaurant, you come to expect that the family eating at the next table over will be using a fork and a knife. In a another example, it is not acceptable to show up at a family wedding wearing a Hawaiian shirt and Bermuda shorts.

The Catholic Church is no exception to these norms. It would be a strange start to Sunday Mass if the priest began processing down the aisle in a Halloween costume. As a Church we have come to assume and expect that our priest will begin Mass dressed in a certain manner.

The question then becomes: Why does Father wear what he wears at each Mass? And what is the history behind his style of dress?

Interestingly, you would think that the priestly vestments of today would find their origins in the ceremonial dress that is described in the Old Testament. For instance, in Exodus 28:2-4 we read: “For the glorious adornment of your brother Aaron you shall have sacred vestments made. Therefore, tell the various artisans whom I have endowed with skill to make vestments for Aaron to consecrate him as my priest. These are the vestments they shall make: a breastpiece, an ephod, a robe, a brocade tunic, a turban, and a sash.”

Instead, the beginning of the holy vestments of the Christian Church came from the everyday garb of the Greco-Roman world. At the heart of this first-century dress was the tunic and the mantle.

The Greeks believed that the tunic that draped from the shoulder was symbolic of the body and its movements. They believed that this enveloping cloak around the body with the head in the center expressed the spiritual and intellectual perfection of man.

In the Roman world, during the second century, the dalmatic, which was a loose, unbelted tunic with very wide sleeves, came about. It was the outer garment worn over the long white tunic. Interestingly, it was striped and for the most part is the outer garment still worn by Catholic deacons today.

By the fourth century, garments worn at liturgical functions had been separated from those of everyday life. Priests could be distinguished by certain ornamentation added to the everyday dress. It was also at this time that the stole began to be used as official symbols of the holy priesthood.

The first mention of a special liturgical garment for sacred worship comes from Theodoret of Cyrus (d. c. 457). In his writing on Church history he noted that, in 330, Emperor Constantine presented to the new church in Jerusalem a sacred robe which was to be used by the bishop at baptisms and the Easter Vigil.

Documents during this time also reflected the fact that many were divided on the question of special liturgical vestments. For instance, the early Christian author Tertullian rejected special dress while Clement of Alexandria advocated it. Pope Clement I, during his pontificate in the first century, noted, “Bishops should be distinguished from the people by costume but not doctrine.”

By the ninth century, the plain vestments of old tended to be more and more elaborately decorated. It was here when pontifical gloves appeared. The miter or the ceremonial headdress most commonly seen on the heads of bishops came about in the 10th century. Liturgical shoes and stockings worn by bishops and cardinals appeared in the 11th century.

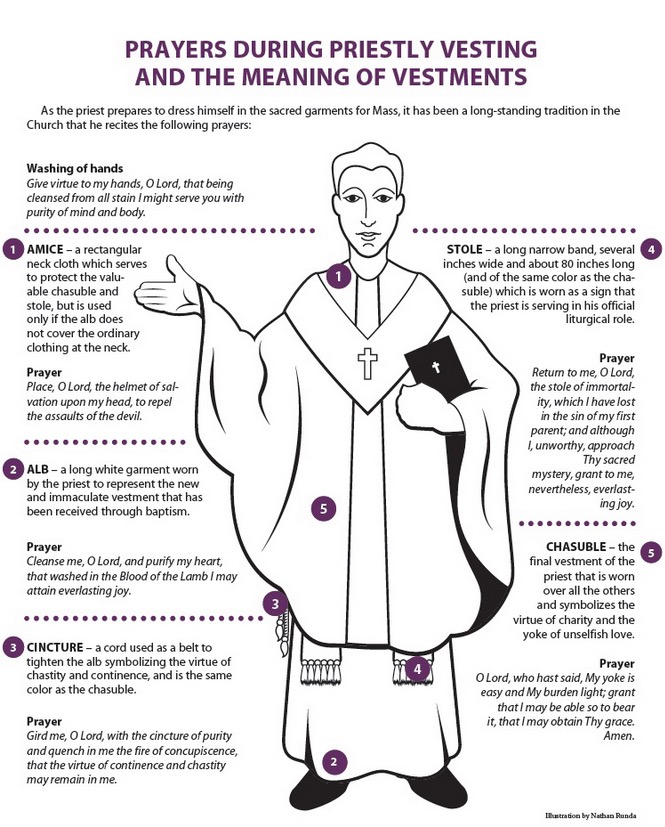

The priest of today who is vested for Mass is a wonderful witness to these historical roots. The fact that the sacred vestments were not worn in everyday life from their beginnings shows that they have possessed a liturgical character.

Today the draping form of the vestments such as the alb, the dalmatic and the chasuble puts the emphasis on his liturgical role. As such, the priest’s body is “hidden” in a way that takes him away as the center of the liturgical action and recognizes the true source and summit of the celebration, Jesus Christ. The priest thus dons the vestments not in his own name by rather in persona Christi.

A priest of the Latin rite today, then, wears the vestments that are prescribed by Church regulations, in keeping with the norms established by the local bishops’ conferences and especially the regulations given by the General Instruction of the Roman Missal, which stipulates that the required vestments are to signify that “in the Church, which is the Body of Christ, not all members have the same function. This diversity of offices is shown outwardly in the celebration of the Eucharist by the diversity of sacred vestments, which must therefore be a sign of the function proper to each minister. Moreover, these same sacred vestments should also contribute to the decoration of the sacred action itself.” (no. 335).

The GIRM adds, “It is fitting that the beauty and nobility of each vestment not be sought in an abundance of overlaid ornamentation, but rather in the material used and in the design. Ornamentation on vestments should, moreover, consist of figures, that is, of images or symbols, that denote sacred use, avoiding anything unbecoming to this.” (no. 344).

Liturgical Colors

It starts with purple and ends with green, and there is a white and red in between. What do the different colors used by the priest signify? As outlined by the Church, different colors represent different liturgical seasons. Since around the sixth century, the primary liturgical colors have been green, white, purple, red and black.

Green signifies Ordinary Time in the Church. It must be noted that the shades of green can vary. For instance, the green of spring is a different shade than that of November as the Church year ends.

Purple is worn during Advent and Lent, representing the penitential sense of those seasons. Similar to purple is the color rose, which is worn just two Sundays throughout the year. First is the Third Sunday of Advent, otherwise known as Gaudete Sunday. During Lent it is worn during the Fourth Sunday, otherwise known as Laetare Sunday.

White denotes times of great celebration as seen in the Christmas and Easter seasons. White vestments are also worn at baptisms, weddings, ordinations and feast days of the Lord, the Blessed Mother and saints who are not martyrs.

Red implies the blood of Christ, the Holy Spirit and the martyrs. It is put on by the priest on Pentecost and for confirmations.

Black, rarely seen, can be worn during the Office of the Dead. It may also be worn on Good Friday.